“When someone is dying and you count down to someone’s last breath. To see the colour drain from the face of a loved one. To see the body still and calm after so much wretched pain and suffering, that is powerful. The silence lingers.”

‘This is a book of photography and text from 2015 and 2016, and there are four deconstructions within it.

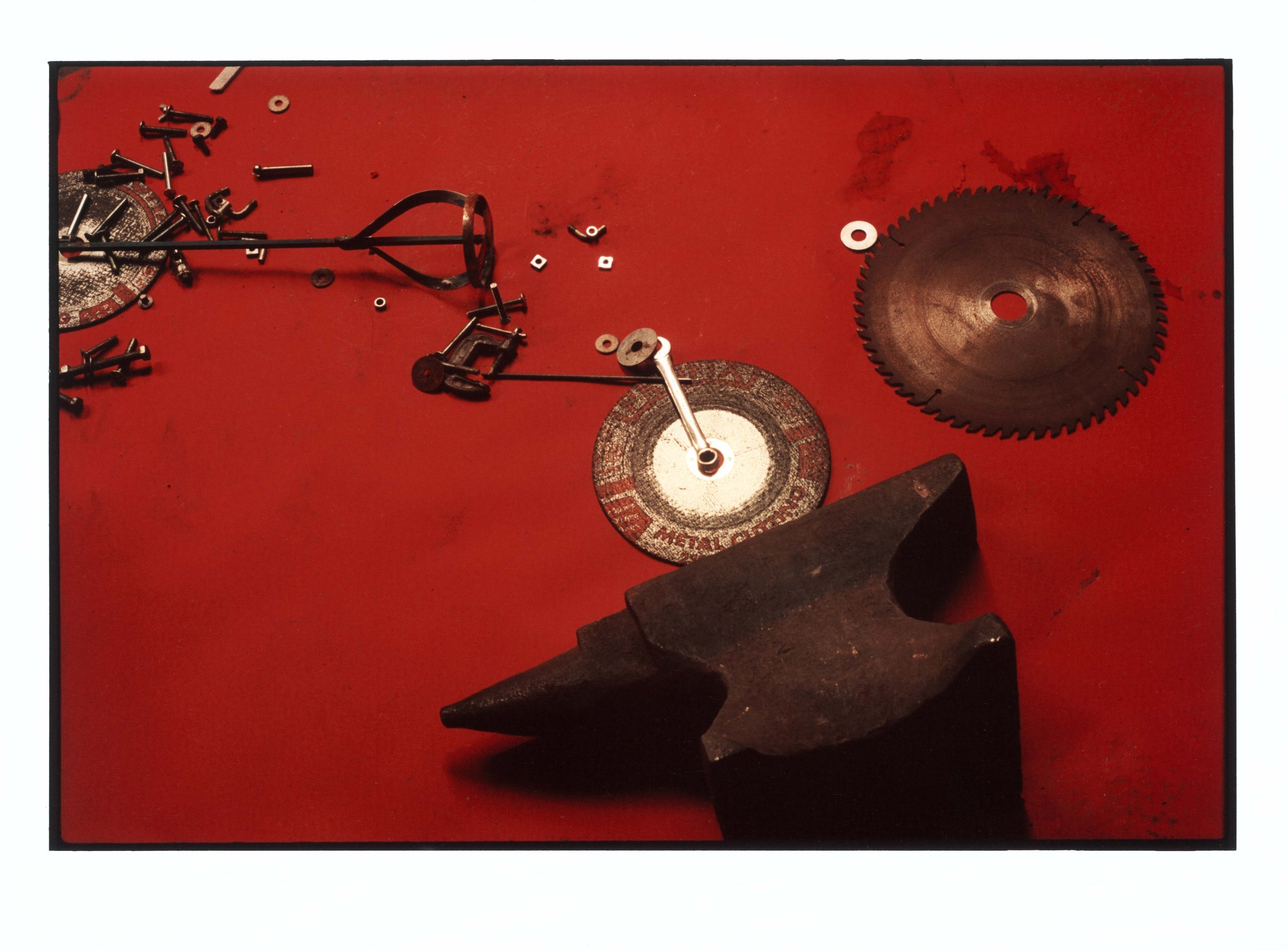

The first deconstruction is of my father’s physical being. He had been diagnosed with prostate cancer and was undergoing rigorous chemotherapy treatments. Whilst dealing with the intensity of these, his arms and hands began freezing. He was a carpenter and he was struggling to hammer, cut and plane. It agitated him. A specialist diagnosed him as having Parkinson’s Disease. A diagnosis he found even more brutal than the cancer. He lost confidence in his work and the freezing episodes put him at risk of losing his driving license.

…

The second deconstruction in the book is my own. My father was my absolute hero. I was in despair. I was in pieces during this period. I sought solace in masochism and excess because I couldn’t face the pain of seeing my father die. I saw death and religious iconography everywhere.

The text my father wrote over the course of his death is a third deconstruction. The hospital suggested he kept a medical journal of his day-to-day dealing with illness. It’s him breaking down the experience in forced, painful diaristic accounts of his body shutting down.

Around the time leading up to the death was my frenzied expression and plea for help in 2016. I often met people away from home in an enclosed private setting. The world was muddy, and I was nihilistic.The process soothed me as I searched for meaning.

The last deconstruction is the photography. With each hand printed photographic exposure, with each chance to catch the essence of something that was being pulled away from me, I wanted tangibility and texture. The drapes thrown over the chairs in the living room. His workman’s yard – the metal and the rust. The nuts and bolts of a life falling apart.

It was the first time in my life I had witnessed death. I was in denial for a long time, simply not believing the day would ever come. Then before you know it, the wind is taken from my sails. It was about the early morning when the fatal time came. The ambulance arrived, Dad got rushed into hospital in a frenzied climax in the last moments. I got to say goodbye, hold his hand and be close to him.

Grieving is a long slow process and at the very beginning, it is all-encompassing. As you evolve, the aftermath gets easier and I began fixing myself up. Seeking help and letting incredible people into my life.

A year later when tidying things away I found a bloody tissue in Dad's dressing gown pocket. I kept it stored away in a 35mm film cassette. It moved with me from home to home. As a way of holding on. I had it photographed forensically in a science lab. I wanted to find him metaphorically in another world. In search of awe. An essence of his existence in an abstract form. I photographed relentlessly, the otherwise tiny tissue came to life with fragments of his DNA magnified quite beautifully under the lens.

When Someone is dying and you count down to someone's last breath. To see the colour drain from the face of a loved one, to see the body still and calm after so much wretched pain and suffering, that's powerful. The silence lingers.

I can't accept that there isn't something greater out there after death. I parted with my Dad's tissue. I placed it carefully in a whisky bottle and set it out to sea. I wanted to close this chapter on my life and set the memory free.